Without really intending it I have somehow found myself in this wonderful rhythm where I seem to make it up to the PNW once a year to see friends and play outside. Gabe and Liza are always nice enough to play host as I flitz in and out: their home being a perfect base for work, play, and eating delicious homemade goods. This time, however, I had managed to get Gabe to agree to a week of alpine climbing with me and I was very excited. Gabe and I have a long history of fun climbing adventures together but in recent years he has been won over by the convenience and quality of PWN mountain biking and claimed that he was not in the best climbing shape. I knew Gabe’s ability to perform (and suffer) off the couch and was eager to see what we could do together.

The forecast looked great leading up to our planned week so we brainstormed ideas. Gabe, a fan of obscure trip reports and always one to do his research threw out a few options, the two most appealing being Megalodon Ridge on Mt. Goode, and the Gunrunner traverse in the Gunsight range near Glacier Peak.

Megalodon Ridge was first climbed in 2007 but has only seen a few additional ascents since. It is a long ridge traverse (which I love), takes you to a classic summit (Mt. Goode), and is a fairly easy grade technically (useful because Gabe wasn’t confident in his ability to climb much harder than 5.10). All around it seemed like the perfect first objective.

Traditionally ascents of Mt. Goode, including prior reports we found on Megalodon Ridge, start off North Cascade Highway at the Bridge Creek Trailhead but Gabe proposed a more interesting idea. We could take the ferry across Lake Chelan to Stehekin where we could then stash some extra food and equipment. From Stehekin we could get on the PCT and approach Mt. Goode from the south. While this added a bit of mileage compared to the northern approach, it was all along the PCT which would make the actual difference in effort minimal. More importantly, after climbing Mt. Goode we could go back to Stehekin, retrieve our extra food and gear, and then hike into the Gunsight Range, allowing us to conveniently link two fairly remote regions of the Cascades in a single trip!

We made a half-hearted attempt at work on Friday but quickly gave in to the more interesting work of organizing food and gear for the week. By 7pm we were packed and on the road to Chelan.

We made it most of the way before stopping to camp in a pullout somewhere near Leavenworth. We drove the remainder of the way early the next morning and did a final rushed gear shuffle in the ferry parking lot with just enough time to catch the 9am ferry to Stehekin.

The ferry ride was an absolutely incredible way to start the day. The wind off the lake was cool and crisp and the sides of the lake quickly grew from low-lying foothills to steep mountainsides, the peaks towering 5,000 feet above the lake. I had read that Lake Chelan was 50 miles long but the true size of the lake did not really set in until we had been motoring across it for over an hour and the end was still nowhere to be seen. It really felt like the perfect start to a grand adventure.

The peace of the boat ride ended as soon as we reached Stehekin. Stehekin offers a bus that ferries PCT hikers the 11 miles to and from town. It was scheduled to leave town 20 minutes after we arrived in town so we rushed about to find a place to stash the gear and food we weren’t planning on bringing for Megalodon Ridge. We ended up getting confirmation from a ranger that it was okay to leave stuff in one of the bear boxes that are scattered throughout town so we did a final frantic check of the gear and then ran to catch the shuttle out of town.

Once on the bus we were finally able to relax, all of our transit and connections now being done. The bus made a stop at the Stehekin Pastry Company so we were able to stock up on some last minute goodies for the day. We arrived at the trailhead around 12:30pm, hoisted our packs, and got ready to set off into the woods.

We quickly joined the PCT which made for nice easy travel. It was quite hot and humid midday, but the deep forest did a pretty good job providing shade and we were able to find a few trickles of water to wet our shirts and stay cool. Gabe is just as fast a power-walker as I am so we made good time and in two hours we had covered the seven miles to where the North Fork Bridge Creek trail splits from the PCT.

The trail grew rougher as we headed up the valley towards Mt. Goode. The lower flank of Mt. Goode extends all the way down to the PCT so we got a real good lesson in the size of the mountain as we hiked another two and a half miles up valley.

Eventually the trees thinned out and we found ourselves looking up at the drainage that would give us access to the Megalodon ridge. A nice looking talus slope appeared to lead up from the creek on the far side, but the area between us and the creek was filled with thick vegetation.

We set about looking for passage through the green sea and eventually identified a faint game trail that seemed as good a place to enter as any.

The bushwhacking ended up being pretty tame by Cascades standards, that is until we tried to find a place to cross the river. The river was lined by extremely dense slide alder which made it impossible to determine the quality of the crossing until we schwacked down to the river bank. We repeatedly forced our way down to water level, only to find the area not cross-able for various reasons. We would then thrash our way back into the slide alder and traverse upstream until we found another potential candidate and repeat the process. Eventually, however, our determination paid off and we stumbled out of the alder onto a little rocky beach that overlooked some deep-but-calm looking water. Not looking for any more fights with the alder we decided to give it a shot.

By some miracle (or more likely because someone else had crossed here previously) we found a perfect stick on the shore that we could use for balance. Gabe went first. The water quickly rose above his knees and onto his upper thighs. With the help of the stick and some careful footing he was soon on the other side. He threw the stick back across the river like a spear and I was able to follow in his footsteps. Before departing we threw the stick back across the river in an attempt to limit our karmic debt to the mountains. With some care and luck the crossing was manageable, but I’m certainly glad the water levels weren’t much higher or I think the crossing could have been pretty sketchy.

The far side of the river was much less vegetated and we were able to locate the talus slope almost immediately and then enjoy the easy talus highway up onto the flanks of Goode.

We followed the creek bed for about 1,000 feet of gain until we reached the obvious chockstone waterfall described in the Jeff Wright trip report. I had been worried that this part of the route finding would be challenging, but it ended up feeling like a pretty intuitive time to leave the creek bed because looking upstream it was clear that there might be no more opportunities to cross the creek and work up climber’s right for a long while. We loaded up as much water as we could carry and then started up the slabs to the right of the creek.

The slabs ended up providing nice easy travel, mostly 3rd class with solid rock and, most importantly, no bushwhacking.

After a little over 500 feet of vertical gain the slabs turned into steep forest which abutted a cliffband. The Wright’s trip report calls out a 60m buttress on the approach and describes it as “super loose and scary” so we felt pretty pleased with ourselves when we found a mellow path of 4th class up through the cliff and back into the forests above.

We should have known better than to second-guess beta from a Wright trip report. A short ascent through the forest finally brought us to the ridge. We thought our day was close to being done when we suddenly got view of a rock buttress up ahead. Unlike the lower cliff, there was no easy passage through this one. We traversed a bit to the left and right but it was obvious there was no good way to go around the cliffband. Feeling some shame we realized that this was definitely the buttress described in the trip report and we weren’t feeling too psyched on scrambling up through it.

We discussed pulling out the rope but we were tired and it was getting late in the day (always two factors to rely on for making important decisions) so we decided to poke up the cliff a bit and see if we could find reasonable passage through it without pitching it out.

A series of delicate traverses on decent rock down low lead us to a dirty ledge system at about 2/3 height. We traversed back and forth along crumbling ledges for a bit until we found a crack system we were willing to commit to. The climbing in this upper third was quite scary, full of loose blocks, dirty cracks, and brittle half-dead trees, but it was just blocky enough for us to ignore the exposure and we pushed on.

To our relief the angle soon began to kick back and we were soon on top of the buttress in one piece. By now it was 7:30 and we were very ready for dinner and bed. Luckily the ridge above contained no more obstacles and we continued up for another 500 vertical feet until the ridge flattened into a beautiful small clearing. We had found our bivy spot.

There was no running water at this spot but luckily we had enough left over from the fill-up at the chockstone waterfall to tide us over for the night. We could see some snow patches above so we were confident we could find water fairly quickly the next morning. We unpacked our bags and settled in to enjoy the views.

It was absolutely blissful to hang out and eat some leftover pizza. For a variety of reasons, usually permits or time constraints, I basically never bivy during my mountain adventures. Either it’s a car-to-car mission or I’m back at some backcountry basecamp at the end of the day. This was really my first time doing a true bivy out in the mountains and it had me wondering why I don’t do it more. Without any stress of a rough night ahead we watched the shadows grow long and the sun dance across the peaks. There was no sign of humans in any direction and it felt as if the whole world was ours.

Ours and the mosquitoes. As the sun dipped below the horizon the wind dropped to zero and suddenly clouds of mosquitoes appeared. We crawled deep into our sleeping bags, desperate to escape, sweating away with clothes over our faces to try to keep the buzzing hoards away.

It was impossible to sleep, in between the incessant buzzing and steady bites, but the silver lining is we were awake to enjoy a final show as the clouds were illuminated by the last light of the day.

Eventually a slight nighttime wind drove off the mosquitoes and Gabe and I were able to drift off to sleep. We awoke around 5:45 the next morning with the rising sun.

We polished off the rest of our water upon waking which made it easy to motivate to get our day started. We packed up our stuff and started up the ridge in the hunt of water and grand adventure.

The Wright’s beta about water from the snowfields beneath the start of the technical climbing proved accurate and we paused for a couple of breakfast bars before eying up the terrain above us. It seemed like there were a number of different places to gain the ridge but we ended up following some mellow ledge systems up through beautiful white granite uphill of some darker, chossier looking rock. This may have been our first asterisk of the ascent because it looked possible to join the ridge lower, in the dark colored rock but we were happy to sacrifice a bit of purity to get on the ridge as efficiently as possible.

The climbing on this initial section was what alpine dreams are made of. The rock was quite good and the ridge was just steep and narrow enough to be interesting without proving overly exciting.

We soon got to the point where the ridge joins the headwall to the top of tower 1. From afar this wall of rock had looked steep and quite intimidating but as the angle kicked back we were pleased to find that the good rock continued. The ridge merged into the headwall and we continued to flow upwards on pleasant 4th class terrain.

We reached the top of tower 1 about two hours after leaving camp and feeling pleased with our progress. This optimism quickly faded when we saw the terrain ahead. Ahead of us stretched a jagged ridgeline composed, a far as we could tell, of crumbling, exfoliating rock. The climbing looked involved, exposed, and most of all committing. It was clear that with our super light rack (a couple nuts, singles .2-2, and 6x slings) bailing down off the ridge would be outrageously difficulty if not outright impossible.

But the weather was bluebird and felt perfectly stable and we still had close to 12 hours of daylight remaining so there was no reason not to push on. We grabbed a quick snack and then started the traverse north along the summit ridge to where we could drop off the backside of tower 1.

It was immediately clear the tone had changed. Gone was the nice solid light-colored granite, replaced by a more crumbly lichen-covered variety. Although the traverse to the top of tower 1 was short, there were several heads-up moves, including one especially exposed step-across to connect two narrow ledge systems.

Reaching the end of the tower 1 the ridge dropped near vertically for several hundred feet and we immediately decided it was time for the rope. We followed the Wright’s suggested approach of down-leading (and then down-following) the ridge due to the traversing and broken nature of the descent. This worked well enough and after two “pitches” we found ourselves safely at the bottom of the tower. The rock was extremely loose in places during this descent and it would have been very stressful to try to navigate this down climb without a rope. I’m not convinced that downclimbing was better than rappelling this ridge, I think with some care you could configure the rappels so the angles and pulls were manageable, but downclimbing is probably the more reliable and lower-variance option (and had the added benefit of not leaving behind any of our already-slim rack).

We put away the rope and started up the next little gendarme. Looking back at other trip reports it appears that most groups traverse directly on the ridge over the top of this gendarme but we ended up following a broken ledge system out to climber’s left partway up the ridge and then contoured around the gendarme back onto the side of the main ridgeline. Another possible asterisk for our ascent, but it worked well enough.

From there we started the long traverse to the headwall of the SE summit. This section of the day was fairly unfun: wandering and exposed climbing on crumbly choss. Perhaps it would have been better if we had stayed closer to the true ridge rather than dropping down prematurely to bypass the gendarme, but I think either way eventually the terrain pushes you off the ridgeline and onto the face beneath the headwall. We climbed slowly and mostly in silence, focused on testing every handhold and foothold.

Eventually it became clear that we were under the headwall pitches (the route finding here was more obvious than photos would suggest). We scrambled up several hundred feet of choss until it became obvious that it was solid 5th class terrain above. We found a tiny little ledge, tossed a single cam into some suspect looking rock in a half-hearted attempt at a belay, and unpacked the rope to prepare for the only real roped climbing of the route.

Gabe took the sharp end and set off into the crack system above. The crack quickly grew too large for the medium-sized gear we had brought and I watched nervously as Gabe grunted upwards, doing his best to jam his soft trail-runners into the wide crack, with only a single cam attaching us to the mountain. Gabe once again demonstrated his remarkable talent at off-the-couch climbing and managed to dispatch the pitch in his tennies, finding only a single piece of adequately sized protection along the way. I took the time to throw on my climbing shoes and then followed him up.

Joining him I grabbed the gear and then started up the supposed “crux pitch”. The climbing on this pitch was actually fairly high quality. With a heavy pack I was psyched to have a rope and climbing shoes on, but 5.9 rating felt fairly accurate. This pitch was also fairly short and I made it to a little ledge and brought Gabe up.

We were swinging leads which meant that Gabe had the misfortune of getting the final pitch to the SE summit. This face was basically unprotectable and Gabe only found a piece of two as he quested upwards. Luckily the climbing was quite easy and I started simuling behind Gabe once I felt the rope go tight and he brought us to the SE summit in one long pitch.

It had taken us around 4 hours to traverse from the top of tower 1 to the SE summit so we stopped for some food and water. It felt like a nice milestone reaching the SE summit; although there was still a bunch of jagged ridgeline ahead the summit looked noticeably closer. More importantly, for the first time since we had started the traverse to the SE summit it looked feasible to bail if we had to. Things were still going well and we were still on schedule to finish well before dark, but it definitely relieved a bit of the pressure to know that if we experienced some unexpected injury or weather change we could likely get off the mountain in one piece.

Properly refueled we scrambled down off the SE summit and started to traverse a short section of scree slopes that wrapped around and brought us to the base of the final ridge up to Black Tooth Notch. The Wright trip report had made the remaining ridgeline sounds fairly trivial but we felt some real trepidation looking up at the mess of crumbly rock we still had to navigate.

We started up the ridge, scrambling over a couple of gendarmes.

The rock was, you guessed it, subpar, and all the focused scrambling was beginning to wear on us a bit.

Up until this point the terrain seemed to at least loosely match what we expected from prior trip reports. But as we made our way over a series of gendarmes we found ourselves confused by the lack of recognizable features (and our discovery of several involved sections that felt worth of mention in a detailed write-up).

We eventually ended up in a steep choss-chimney after bypassing another gendarme. Seeing no where to continue traversing we followed the steep chimney upwards until it pinched down and steepened, the way ahead blocked by overhanging terrain. Luckily at this point we noticed a section of lower angle slab that would allow us to exit the chimney on climber’s left and continue our traverse. The moves looked dicey and there was mega exposure so we opted to pull out the rope again and I started leading out from the chimney. I made a few slab moves that made me glad to have the rope, passed an old pin that indicated at least someone else had found passage this way, and then found easier terrain that allowed me to continue around the corner.

I was relieved to see reasonable 4th and easy 5th class terrain ahead so I continued with Gabe simuling behind. A series of convenient ledge systems brought me around to Black Tooth Notch. After the unexpectedly difficult route finding in this final portion, I was relieved to know we were back onto well traveled ground.

I belayed Gabe into the notch and then set off again, taking us to the summit in one long simul block. The climbing on these upper pitches of the NE Buttress were utterly joyful. After so many hours unroped on rotten rock it felt wonderful to turn the brain off and romp up some solid granite.

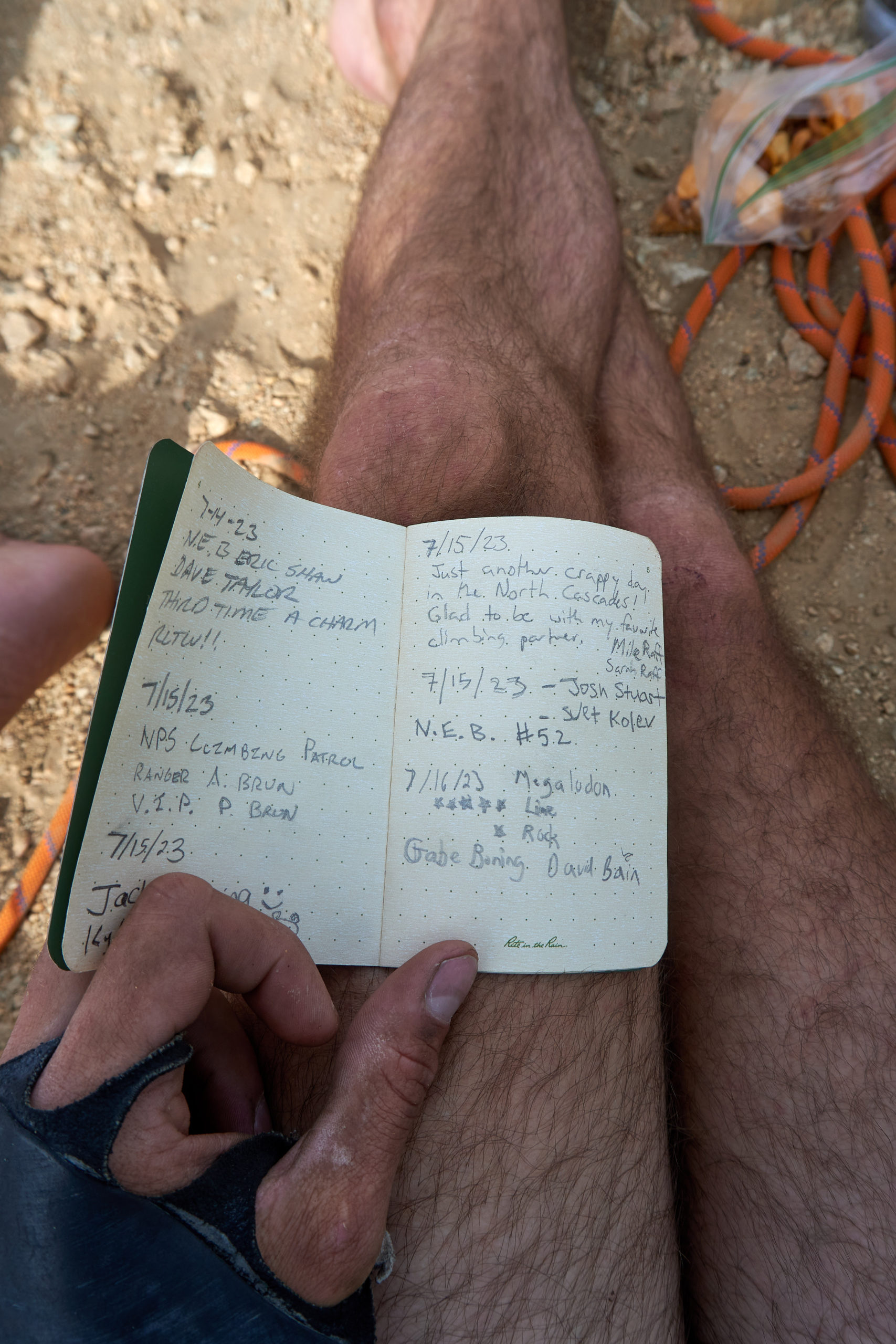

We reached the summit around 6:10pm and savored the amazing summit. The summit platform was flat and sandy, undoubtedly terraformed from decades of planning and unplanned bivies, and provided 360 degree views of the Cascades. The weather was perfect, windless with no threatening clouds, and we sat perched atop our alpine crow’s nest flipping through the logbook and soaking in the satisfaction at our accomplishment. It certainly looked quite far looking back along the ridge we had just traveled.

We even found an uncrushed Mega Goldfish™ to pose with the very mega ridge.

We spent close to 45 minutes on the summit appreciating the views and trying to get up the motivation to move. We even discussed bivying on the summit but decided against it due to lack of water and paranoia about wasting perfect weather not descending.

Eventually we summoned the willpower to descend. Three easy rappels brought us back down to Black Tooth Notch the way we had climbed up.

The descent down the southwest couloir proved fairly straightforward, especially in comparison to all the day’s challenges and pretty soon we hit the traverse above the final cliffband and from there slid down loose scree to a little meadow below.

The sun was starting to get low in the sky and the meadow seemed like a perfect place for another bivy so we decided to stop there for the day.

We laid out our pads on the soft mossy grass and sank back onto them to enjoy the last few moments of daylight. The peaceful gratitude that comes from knowing you’re safely out the other side of a big adventure is a special emotion that is unfortunately directly tied to the magnitude and risk of said adventure. It’s an emotion I know I should only get to experience on rare occasions. I did my best to be present and take it all in.

The winds picked up over night and we woke up the next morning to moody clouds and a light mist. We took a moment to recognize how glad we were that we hadn’t decided to bivy on the summit and then threw our gear into our bags and began the long slog back into the valley.

The rain made the steep tussocks extra slippery so we carefully picked our way down the upper slopes around a few cliff bands.

Eventually the slope angle flattened slightly and we found a faint climbers trail that we were able to follow the remainder of the way back down to the valley floor. Looking back up we could see the upper flanks of Mt. Goode wrapped in clouds, adding a dramatic and mysterious air to the mountain.

Back on the trail it was a quick 13 mile hike back to the trailhead where we made it just in time to catch the midday bus back into Stehekin.

Back in Stehekin we waffled on what to do next. We both felt pretty fatigued from our Mt. Goode adventure and the idea of turning around and doing a long bushwhacky approach to a remote corner of the Cascades to climb in the Gunsights seemed pretty unappealing. On the other hand it felt pretty lame to bail on our big plan when we were all the way out in Stehekin stocked up with gear and food. In the end we decided to bail, justifying to ourselves that there were other parts of the Cascades we wanted to check out. We caught the afternoon ferry back across Lake Chelan and then started the drive over to Washington Pass.

I’m not going to do any detailed write up for the remaining adventures but we had an awesome time climbing The Hitchhiker on the South Early Winter Spire and the mega classic West Ridge of Forbidden Peak. After a long and stressful day of traversing mega-choss, it was a wonderful change of pace to climb on perfect, well-traveled rock.

Despite Megalodon’s somewhat questionable rock quality, I’m extremely glad that we decided to climb it. Prior to this trip I hadn’t done any technical climbing in the Cascades outside of a trip up Mt. Stuart so it was fun to dive in and climb a big route right in the heart of the Cascades. The line is extremely aesthetic and offers a perfect level of routefinding and climbing challenges to make for a satisfying summit. Now I just have to make it back for the Gunsight’s!

Leave a Reply